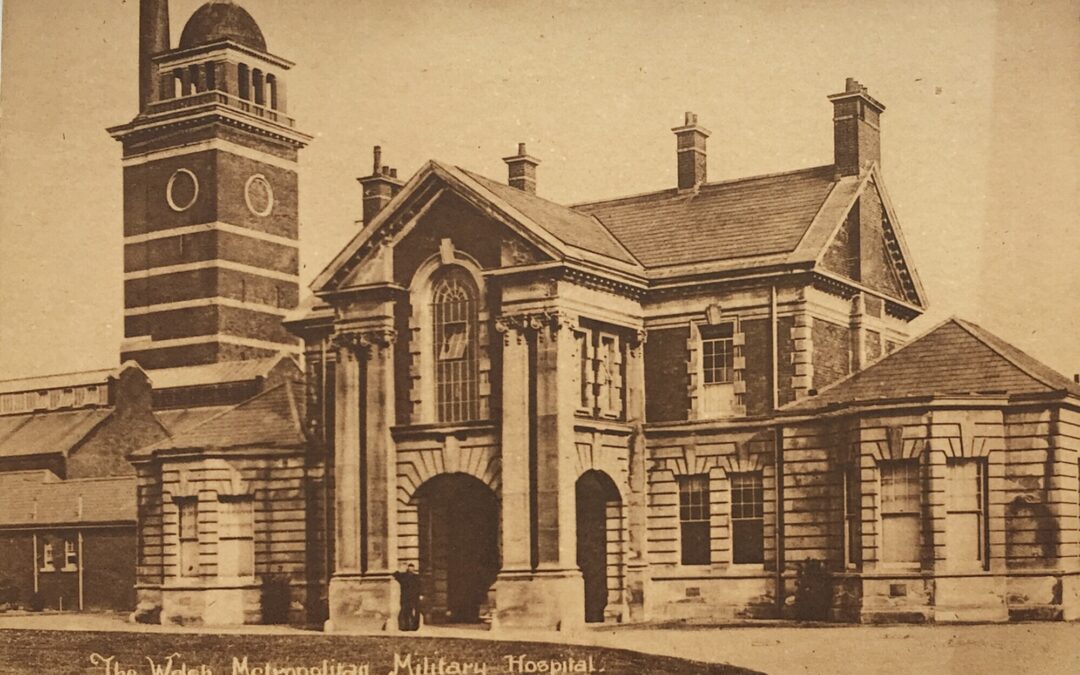

Photo courtesy of the Whitchurch Hospital Historical Society.

I always did a slow burn at how little the lives and welfare of the psychiatric patient counted for in our culture, but it was hard to see what real improvements one could make; a thorough change of attitude was needed first of all. I tended not to care too much about the presence or absence of luxury in my own surroundings at that time—having been brought up in the ‘plain living and high thinking’ academic tradition—but I felt that far more should be spent on treatments and research. The institutional nature of the buildings didn’t trouble me as much as the feeling that the patients, particularly the chronic ones, counted for so little in the scheme of things.

Acutely mentally ill people in Whitchurch got reasonable management by the (low) standards of the time, considering our groping after knowledge and the early state of much of what we had to offer. Many staff on the acute wards were really caring and tried to give people who were extremely ill—sometimes wild, disinhibited and dangerous—a sense of dignity and selfhood. There were regular ward rounds, every day for the juniors, once or twice a week for the consultant. There was a constant watch for suicidal or self-destructive behaviour and planned care, at least in theory, was the norm.

That said, I didn’t find Whitchurch Hospital particularly well equipped or forward-looking. The hospital housed the Academic Unit, which later moved to the newly built University Hospital of Wales but was still very much part of the wider service. There had also been some sort of medical research unit within the hospital and a sense that the staff traded on past glories. Senior staff certainly seemed to feel they were superior and more advanced than other places and may have been partly so. I found Whitchurch to be in many ways rather insular and backward compared with the facilities and attitudes of some of the places in which I had been working or with which I had had close contact. I was tactful enough not to say this, but early on I recognised that it was vital to get one of the posts on East One, the Academic Unit, if I was serious about continuing my training, though at first I had virtually no contact with it.

I’m glad I held my peace about this because I had not been long in Whitchurch before the Ely Hospital scandal broke. Although the dreadful conditions in that ‘subnormality hospital’ (as they were then horribly designated) a mile or so from Whitchurch, were widespread, almost universal, it happened to be Cardiff that hit the headlines this time.

Of course, such public recognition was absolutely essential—and the conditions of such appalling care needed to be exposed country-wide. I did though feel sorry for Dr Jenkins, the Superintendent, who I knew only slightly. He had great support from the colleagues in Adult Psychiatry, rightly in my view, because it was unfair to make him the main scapegoat. He had been trying to bring the problems up with the health authorities for many years, perhaps not making enough fuss, but how do you change a whole culture? The disgusting conditions eventually exposed were, country – no, world-wide. Dr Jenkins was made a scapegoat to save the administrators and politicians.

There were many good researchers writing on the bad effects of institutionalisation at that time and many lessons were being learned. It was an exciting time to come into psychiatry. Maxwell Jones was bringing in a form of democratisation of the inpatient system. David Clark also brought fresh air into the debates in the psychiatric journals. Scandalous practices were no longer always being hushed up. I was an early convert to the idea that treatments should, as far as possible, be in the patient’s own home or smaller, local units and that no-one should end up living in a large institution.

This brave idea is still only very partially realised. It’s much more expensive, particularly needing teams of much better-trained staff. It is also due to the intransigent nature of chronic mental illness itself, particularly schizophrenia. It was becoming obvious in the 70s that not all the long term symptoms—inertia, poverty of emotion and destruction of the thought processes—were due to the asylums; most could also occur as a result of the psychotic process.

Our early hopes for keeping patients in the community were high but did not produce the brave new world we had expected. The process of ‘freeing’ the patients was very slow, hindered by poorly trained nursing staff, inadequate funding, entrenched public attitudes and the nature of their illnesses. Although much has improved, particularly for those with learning disabilities, the country has never invested the necessary amounts of cash and energy to give dignity of life to people with chronic mental health problems.

Of course we came across the work of Laing, you couldn’t miss him as a young psychiatrist. He was a considerable influence and I appreciated his approach: that madness was simply an alternative form of creativity. The trouble was it didn’t really fit with the sort of cases we had in the big wide world outside London. Schizophrenia, I still believe, is a heartbreaking deformation of the creative process and of the psyche. The disinhibiting effects of the illness can sometimes, at first, release useful strengths but, unless checked, the process can destroy the personality and the life.

Laing also seemed to me, in his psychoanalytic approach, to be confusing the content of the patient’s delusions with the psychotic form of their thinking. The former could lend itself to explanation and at least a little psychotherapeutic help, the latter was intractable without medication. He also squandered the goodwill his early ideas created by his paranoid personality, heavy drinking and arrogance. A shame; he had a lot of influence outside the psychiatric field, with a whole generation of hippies and alternative therapists, and could have done much good.

Medication did indeed damp down the emotions and blunt the feelings. No wonder patients often hated taking their tablets and lapsed once at home. Unfortunately, their freedom to do so could conflict with the rights of others. An extreme example was one of our patients, a young man who lived with his elderly father. In hospital, he would be medicated and sane. Each time he went home he stopped taking the drugs because he felt so much more alive and his symptoms were exciting and thrilling to him. Then his paranoid ideas would develop, mostly relating to his father and expressed in increasingly serious aggressive outbursts. The day he was luckily intercepted by a caller, chasing his father round and round the kitchen table with an axe, the old man at last consented to have him admitted under section for a lengthier period and stabilisation. He was supervised more carefully on discharge, with his father’s heartfelt agreement.

One thing that really annoyed me in those days was that the Board of Governors met every month in Whitchurch Hospital. They heard a report from the Matron and Medical Superintendent and discussed policy. Now I had, and have, no quarrel with that. I am an unusual person in that I will freely admit to enjoying committee meetings, if well conducted. Even the less good ones afford a welcome change from being on one’s feet and rushing around all the time. It’s a good corrective for individual tyranny and can facilitate consensus management.

No, what I objected to was that they always had a very good lunch. Briefly, the smell of boiled cabbage would be replaced by more delicious odours at the front of the hospital wafting from the mahogany mausoleum. “Why can’t they have what the patients on the chronic wards are getting!” I would cry to shocked uncomprehending looks. “It wouldn’t hurt them to have a non-luxury lunch once a month. Why can’t they at least have the bog-standard canteen food? How much does it cost to feed them all?” Alas, no one was in the least interested in my French Revolutionary moments; a sort of reverse ‘let them eat cake’.

Another interesting read. Having had a grandmother who was mentally ill, it’s no picnic.

She had a brain operation. Another woman had the same op and was okay, but not my grandmother. It’s hard to describe her illness, but she would have shouting spells at my grandfather, usually in bed most of the morning, didn’t do anything in the house. Yet, she was intelligent. When she was in good humour very interesting to listen to. After the op the family were told, nothing else could be done so the family had to cope with it. After 35 years of marriage, my grandfather finally left, he just couldn’t take no more.

Thanks for sharingxx

Thank you for your addition to this. Yes – so many individual tragic stories, needing to be heard. I think you’ll like the week’s piece, as I’m telling about one ‘case’ who has done well – of course with her agreement, indeed it’s her wish.