I am finding that putting out my memoirs here, in the form of a blog, is very satisfying. I am delighted—sometimes overwhelmed—at how nice it is to receive comments, both online and personally. I also realise that I may have given a wrong impression sometimes, and can take the opportunity to correct it, as the feedback makes me see certain things I’ve said that might be confusing.

So—regarding my writing about my time in Vienna, and my family history—I think they may have given an idea of a much more elegant lifestyle than we had, or that we moved in some exotic circles. Not really true, my childhood was not at all elegant and our house and lifestyle were mundane and practical, in the ‘academic’ tradition (plain living and high thinking).

Although money was adequate, many of our family friends had more obviously luxurious surroundings. My father’s salary as a Professor was not large until he ‘retired’ (when I was 16) and earned a great deal more as a Consultant in industry. Nor did my mother ever earn anything much by her small private practice as a Psychoanalyst, though both of them were highly respected as individuals. We certainly didn’t ever move in aristocratic circles—I wouldn’t even have wanted to be a ‘debutante’ in England. So the exotic lifestyle of my father’s old friends and the events that came about on the trips abroad were all the more exciting.

I don’t like deadlines very much, so I believe it was the right decision to send out the pieces I had already written, and always have some in hand, vaguely chronological, but being able to juggle the order if it felt better. I will continue to do this, but the process itself has changed my priorities. Many of the things that have happened to me, that I have remembered and written about, can be seen as life’s lessons. It is those—in bite-sized pieces—that I will concentrate on through this strange summer of the pandemic we are going through, with perhaps just a few words of explanation, or mentioning my age, to show that we are leaving out, or putting on hold, great chunks of my life.

*****

I would like to recount here another couple of incidents from my time in med school, which have influenced me for the better throughout my life. The first one is funny, the second one very touching, both are, in my view, beautiful.

The first one was quite early in my time on the wards. Earlier still, at the beginning of my student life, I had been living at home. I would take the train from East Croydon up to Paddington and walk to the medical school through Soho—even more colourful and exotic in its foreign shops and nightlife then than it is now. It would be early, around 8 am, and often in fine weather small groups of ‘ladies of the night’, winding down for their sleep time, would be sitting on the nightclub doorsteps, smoking, gossiping and calling out saucy things to the passers-by. At first, I was embarrassed, but I quickly realised they were harmless and fun.

So when one day, a couple of years later, a Soho lady was brought in to Casualty at the Middlesex Hospital while I was doing a student stint there, I recognised the type, though not of course the individual. She had been severely beaten up by her boyfriend and her face and body were, frankly, quite a mess. The nurses and doctors cleaned her up and sutured some wounds, briskly and professionally with no judgment, as they would for anyone.

She was admitted for what was left of the night and I sat with her through it, for a long time. She held my hand and poured out her life story and her pain and frustration with her abuser. Luckily I was too inexperienced even to make the classic mistake of asking why she didn’t leave him. I just sat and listened, pained, helpless and absorbed, till she slept.

Later the next morning I was with the other students, tagging behind the Important Consultant on his daily ward round. When he got to this lady, he checked with the nurse and told her she could go home and attend for wound dressing later. She thanked him dramatically and then raised herself up in bed and cried:

“But here is the wonderful young doctor who helped me. I owe her SO much!”

I found myself grabbed and pulled into the embrace of this large enthusiastic lady. My feet—literally—slipped from under me and I nose-dived into her huge scented cleavage. I hugged her back as best I could and extricated myself, to see the contained giggles of my co-students, swiftly suppressed by the icy look of the Boss, who harrumphed, glared at me and led a silenced group away.

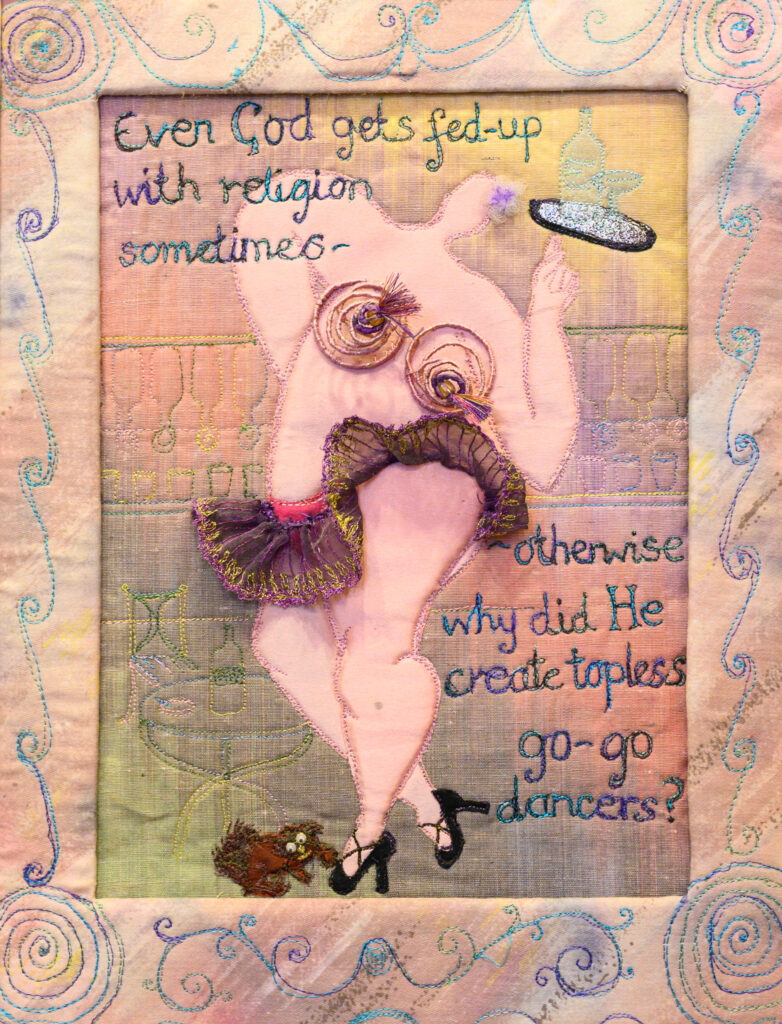

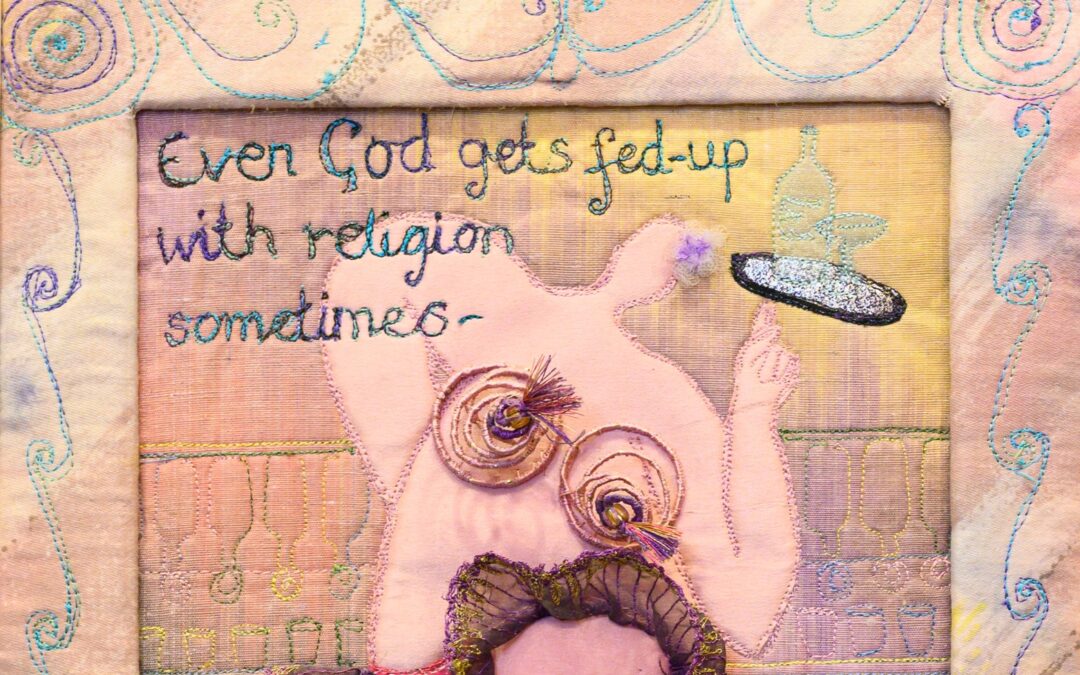

Me in the wrong as usual, I felt. But, years later, she and her ilk became the models behind my ‘Fat Goddess’ series. My favourite is the applique cartoon these Soho women inspired, of a large night club lady, with the embroidered caption: “Even God gets fed up with religion sometimes. Otherwise why did He create topless go-go dancers?”

Towards the end of my time as a med student, I was taking my conventional medical learning much more seriously than earlier. But I had another lesson to learn. A small group of 5 or 6 students were assigned to each ward, mine being Cardiology. One day I was taking a history from a man in his 40s with a very serious heart condition. Having done this, I handed over to the qualified medical team and had a brief chat with his wife. They were childless, Irish Catholics, and had in fact only been married for a couple of years. He was ill enough to be put in a side room on his own and I had no particular interaction with either until an emergency alert went up—he had collapsed. We students were expected to go there, of course, to observe and learn.

Towards the end of my time as a med student, I was taking my conventional medical learning much more seriously than earlier. But I had another lesson to learn. A small group of 5 or 6 students were assigned to each ward, mine being Cardiology. One day I was taking a history from a man in his 40s with a very serious heart condition. Having done this, I handed over to the qualified medical team and had a brief chat with his wife. They were childless, Irish Catholics, and had in fact only been married for a couple of years. He was ill enough to be put in a side room on his own and I had no particular interaction with either until an emergency alert went up—he had collapsed. We students were expected to go there, of course, to observe and learn.

As I got to the door, I saw that his wife, looking stunned and shocked, was sitting outside. There was no way, no way in all the earth that I could walk past and leave her there alone. I knew my real duty was to go in with the other trainees, but I couldn’t. As I sat down beside her, without saying a word, another awfulness hit me. I had—literally—no words to say, nor comfort to give. How could I, a young woman with no direct experience of marriage and loss, say anything? I was being a fool, for nothing. I should be in that room helping—but I couldn’t, somehow, leave her.

I sat there for many minutes, feeling stupider and stupider, I wasn’t even thinking of her, poor woman, but self-immersed in my own uselessness—which still slightly shames me to admit! No role of inner prayer even. After about half an hour of complete silence, the door opened and she was beckoned in, while I slunk away.

Her husband survived for another week, but eventually, sadly, died. I was on another ward by then, a routine changeover. However, sometime later I had a card from the widow, with a photo of him and an invitation to tea the following Saturday.

I went along to their little flat. The lady was warmly welcoming and we had a very nice tea. She gave me a small embroidered tray cloth, which I still have, and talked a lot about her late husband and her plans to return home to Ireland soon.

As I left, she held my hand and asked me if I remembered the day a week before he died, when he collapsed and I had sat outside the room with her—and I indicated that I did. She then said to me, with great certainty, in words I can still hear clearly: “I will never forget how you sat with me and the many wonderfully kind things you said to me.”

We hugged and I went home, stunned. I knew I had not said one single word. Whose voice had she heard, comforting her so well, covering my inadequacy—yet picking up my good intention?

It remains a precious memory and a reminder that there is often no need for words and certainly no need to feel bad. The presence of another is often more than enough.

I think we always think we have to say some words, when really words are totally inadequate. As you will know well now, it’s just sitting with someone either in silence or listening to them as they share their feelings.

I think the problem we have in life, in general, is we cannot cope with silence, we feel we must fill it with something. In a church service, if you ask for prayer and there is silence, people become fidgety, hoping some one will soon pray. Or even if you say we will spend a few minutes in silent prayer.

When someone is going through such an experience you describe no words can make it better, but just knowing someone cares enough to stay with you and listen, and maybe in that silence God is allowed to speak.

Thank you for both stories, the reminder of accepting without judging and the need to be silent.xxx

Thank you again for your welcome support, Diane – Elinor xxx